There are a lot of people studying shark movements these days. It seems like most conferences I go to or web sites I visit have a heavy tracking focus. This is interesting to the handful of us who have been doing this for a while – suddenly what we do is really popular! So why do people track sharks? Some of them do it because it’s cool and interesting, but ultimately it is hopefully useful for more than scientific curiosity.

I have spent the last 15 or so years tracking sharks – why do I do it? Although I also think tracking is cool, fun and interesting my tracking research started out trying to answer a specific management based question: how long do juvenile sharks stay in a nursery area? That research told us how dependent they were on that area and how important it was for their survival. Since then I have done a number of projects that looked at how sharks use space relative to marine protected areas. The driving question: how much is an area that is closed to fishing protecting sharks? To answer that we have to think about how long sharks stay inside the protected area and how often they move in and out.

One of my students, Danielle Knip did a really nice analysis of closed area benefits for pigeye and spottail sharks in a north Queensland bay. What she found was that over the course of 2 years these sharks only spent 22-32% of their time inside the protected area. That means they weren’t getting much protection from fishing. It was an interesting finding but the closed area wasn’t actually designed to protect coastal sharks so we weren’t totally surprised to see such low levels or protection.

A pigeye shark (top) – a close relative to the bull shark, and a spottail shark (bottom). The two species were tracked to see how long they stayed inside a marine protected area.

More recently I’ve been tracking reef sharks to see if protecting a reef protects the sharks that use it. The answer: it depends. That’s a scientist answer for you. We never want to say yes or no until we tell you the whole back story. In this case though, the “depends” actually relates to the species of shark. For species that spend a long time on the same reef they can get a lot of protection from closing their reef to fishing. For example, Mario Espinoza and I recently showed grey reef sharks can spend years on a single reef based on data from two separate sections of the Great Barrier Reef. However, if they spend a lot of time on a reef that isn’t closed to fishing they may be more exposed than average because fishing pressure might be directed to that reef due to closed areas. Things that move more widely though, like tiger sharks, silvertip sharks and bull sharks get much less value from closed areas because they move so much.

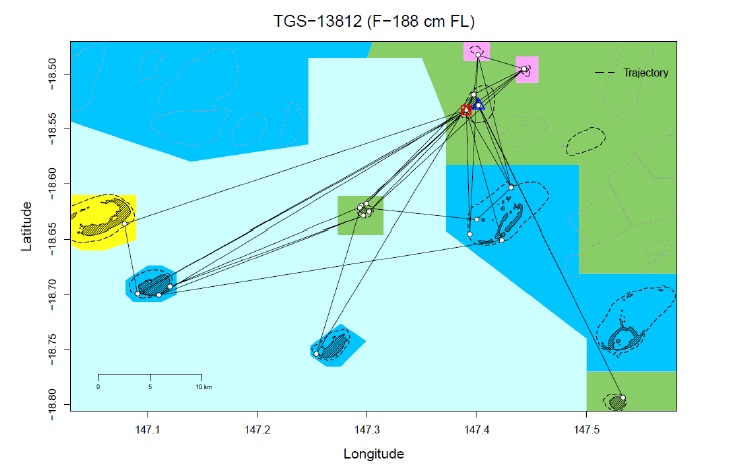

Map showing the movements of a female 188 cm tiger shark moving between coral reefs. Reefs in blue and yellow are open to line fishing, green and pink are closed to fishing. Blue triangle and red square indicate the beginning and end of the track.

So what does all this mean? It means we can’t just use closed areas to protect sharks – a lot of them just swim right out. We have to use other management measures like catch limits to help protect them. The other thing this means is that we really do need to understand how much the animals we are trying to protect move. How long they stay and where they actually go are critical to our ability to get management right.

Papers related to this story:

Heupel MR and Simpfendorfer CA (2015) Long-term movement patterns of aoral reef predator. Coral Reefs 34: 679-691

Heupel MR, Simpfendorfer CA, Espinoza M, Smoothey A, Tobin AJ and Peddemors V (2015) Conservation challenges of sharks with continental scale migrations. Frontiers in Marine Science doi: 10.3389/fmars.2015.00012

Espinoza M, Heupel MR, Tobin AJ and Simpfendorfer CA (2015) Residency patterns and movements of grey reef sharks in a semi-continuous reef environment: evidence of reproductive behaviour. Marine Biology 162: 343-358

Knip DM, Heupel MR and Simpfendorfer CA (2012) Evaluating marine protected areas for the conservation of tropical coastal sharks. Biological Conservation 148: 200-209.